Historical Background

Quick Overview

1850: The McCree family, a household of

farmers who came to Texas with the Peters

colonists, was granted 640 acres of

land in present day northeast Dallas.

1862: John Henry Jones, a Civil war veteran,

was buried on the land that would

become McCree cemetery. This is the oldest

known burial in the graveyard.

1866: McCree Cemetery is founded on a

small portion of the land grant.

1896: McCree’s eastern plot was acquired

and accommodated the Little Egypt

community. Some of the founding families

of this community, the Hills and the

Floyds, are buried within the cemetery.

1930s-1940s: Two congregations held

services in the church by the graveyard.

This included the Cemetery Chapel Episcopal

Methodist Church and the Rodgers

Baptist Church.

1942: Chapel burns down.

1950s: Cemetery is heavily vandalized.

1960s: Development around the cemetery

causes the land to be no longer rural.

1970s-1980s: Residents of the new

neighborhood development encapsulating

the cemetery mention the cemetery was

heavily littered and uncared for.

1986: Texas Historical Marker.

2018: City of Dallas landmark designation.

Early Settlers and the Establishment of McCree Cemetery

The colonization of north central Texas began in earnest in the 1840s. European Americans, primarily from southern and eastern states found offers from land granting companies too tantalizing to ignore. One of the most prominent land agencies, the Peters Colony, promised family men 640 acres and single men 320 acres. The families that settled here helped establish communities now gone (Audelia, Jackson, Breckenridge, Rodgers) and those that remain, including Richardson and Garland. The first to arrive here in the 1840s and 1850s found wide stretches of prairie with high grasses, buffalo, deer, creeks, numerous springs, and the rich, Blackland Prairie soil. As one pioneer noted, in reference to the north central Texas landscape:

You see, the whole of this fine prairie country was before us to select from, and we wanted to take a good look before finally making choice of a section of land. It all looked so rich and green and beautiful that it rather bewildered the heads of families to make a selection [B.J. Prigmore 1891].

That certain families made the White Rock Creek area in present-day northern Dallas their home says much about its promise and beauty. In turn, these pioneering families worked hard to make a living off the land. They established farmsteads, prospered, and formed small communities to provide needed services. It appears they relied on one another for social and economic needs. Families such as the Jacksons, Prigmores, McCulloughs, McCrees, Goforths, and many others shared similar pasts in coming from afar to seek opportunities and establish new lives. In a number of cases, children, grandchildren, and even descendants generations later remained in the area and contributed to the development of twentieth-century towns, cities, businesses, and institutions. On the surface, one has to look hard to see the legacy that these pioneers left behind. Street names, McCree Cemetery, and the names of creeks seem to be all that is left, but without these families, Richardson and Garland might not have developed as they did, and Richland College exists in great part due to the Jackson family. Nearby African American families also built churches that remain to this day, serving the spiritual needs of their founders’ descendants. Research into the archival records left behind provides a glimpse into the backgrounds and immediate experience of the Anglo settlers who made this part of Texas their home in the mid nineteenth century.

The Jackson Family

John Jackson (Section A, Row G, Grave 45), son of a Revolutionary War veteran, and Eliza Brown Jackson (Section A, Row G, Grave 46) left Missouri to arrive in Dallas County in 1845. As a Peters Colonist, he received a 640-acre certificate for land dated November 15, 1850. He died in 1875. The head right became known as the “Jackson home” where the large family often gathered (Figure 11).

A son of John and Eliza, Thomas J. Jackson (Section A, Row G, Grave 42) was two years old when he arrived in Dallas County with his parents. Thomas J. went on to serve in the Civil War as a member of Captain W. W. Peak’s Thirty-First Cavalry, Company A. He married Mollie Nash (sister of Judge Thomas F. Nash) and died in 1910 (Dallas Morning News 1910a, 1910b; FJFf). Other Jackson children included Jeff, Cape, Jimmie, and Ella (Richardson Echo 1933).

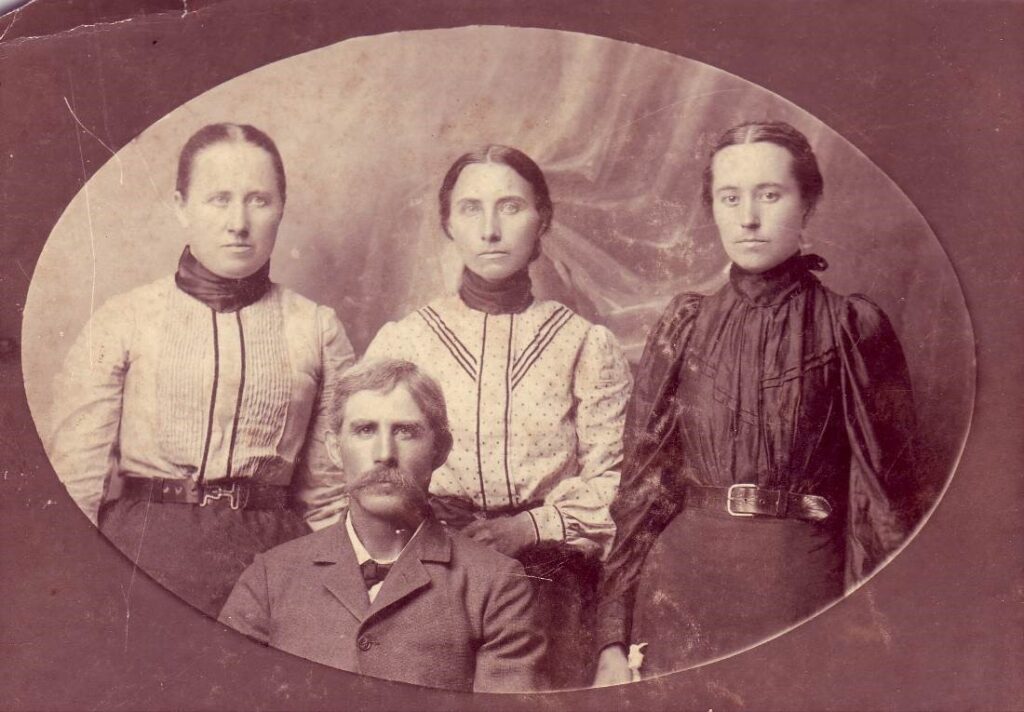

The Prigmore Family

In 1844, Benjamin J. Prigmore (Section A, Row H, Grave 48), age 14 years, arrived in Dallas County with his father, Joseph Prigmore; his mother, Mahala Dixon; and his siblings. The Prigmores built a log cabin and went about planting wheat with only a yoke of oxen to plow the ground. They then built a worm fence, plowed up more land and sowed nearly 16 acres of corn. Joseph Prigmore established a corn mill and served on the first Dallas County Grand Jury, but in 1849, he left for California. Upon his return in 1855, he sold his head right and gathered up his family, with the exception of Benjamin, to go back to California. He returned to Texas again in 1860 and died in 1862 (DPLa).

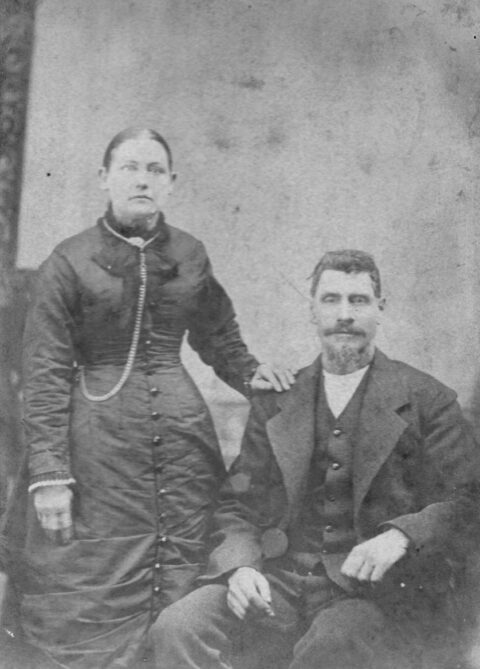

While his family was in California, Benjamin Prigmore farmed until he joined the Army just prior to his 17th birthday and fought in the Mexican War. In 1853, he married Nancy J. Jackson, daughter of John and Eliza Jackson (Figure 12). Benjamin and Nancy Prigmore continued to work on the farm until 1862 when Benjamin enlisted in the Confederate Army. He returned home after the war, at which time he took up farming again on a land grant he received for his service in the war.

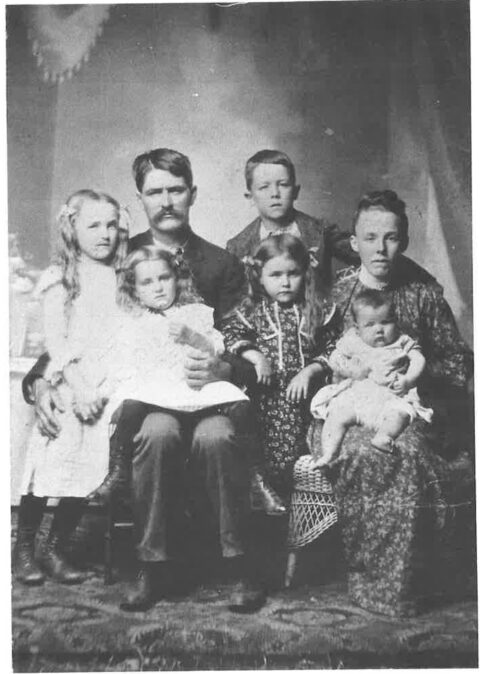

Tragedy struck the Prigmore family on May 26, 1867, when a tornado descended upon their farm, destroying several buildings and killing their oldest daughter, Eliza (buried in McCree Cemetery; row and grave number unknown). As time went on, the Prigmores were able to re-establish their farm and re-build their home. Benjamin and Nancy Prigmore were successful enough to provide farms for their remaining children, who in the 1890s, all lived within the same general vicinity as their parents (Figure 13; see Figure 12). A comment in a biographical sketch, published in 1892, attests not only to the personality of this early couple, but also hints at the importance of social relationships to the overall survival of the burgeoning community. In reference to Benjamin and Nancy Prigmore, it was noted:

At the home of this worthy couple, the stranger as well as the friend received a cordial welcome, and is entertained in true Southern style. Mrs. Prigmore is an adept in [sic] the culinary arts, and knows full well how to spread before her guests a tempting board and preside thereat in a most graceful manner [Lewis Publishing 1892].

Benjamin Prigmore died in 1901 (Section A, Row H, Grave 48); Nancy Prigmore died in 1904 (Section A, Row H, Grave 47) (DPLa).

Additional Families

In addition to the Jacksons and Prigmores, a number of families settled in this area of White Rock Creek between the 1840s and 1870s. These families included the McCulloughs, Crosbys, Bechtols, Brites, Goforths, Dixons, Ethridges, McGaughys, Sloans, Griffins, and McCrees, to name a few. James Willeford Crosby (Section A, Row G, Grave 3) and his wife, Mary Texana Hollingsworth (Section A, Row G, Grave 2), came to Texas in 1876 from Mississippi. They joined James’ father who had arrived two years earlier. Their farm was located near Church Road where they raised seven children: Eva Greem, James Duke, Tildon Barnes (Section A, Row H, Grave 2), John Willeford, Vertie Vera, Ira Virgil, and Alvin Lionel (DPLa).

The McCulloughs included four brothers and two sisters who traveled by wagon train from Kentucky, arriving in Texas in 1845. The siblings were William (and his wife Eleanor Elizabeth [Section A, Row M, Grave 45] and their children), Thomas, John (Section A, Row M, Grave 43), Daniel (Section A, Row M, Grave 44), Hannah (with husband James Newsome) and Fereby (with husband John Henry Jones and their children). Within a few years, most of the McCullough siblings, if not all, had established farms near one another in the McCree Cemetery area, near White Rock and Jackson creeks (FJFd, e). Daniel Bechtol and his first wife came to the area in 1874. His wife, Mahala Biser Bechtol (Section A, Row K, Grave 41), died that same year (Lewis Publishing 1892). Many families lost infants and children. One can assume they were often the result of illness, though the loss of Eliza Prigmore in the 1867 tornado and a hunting accident that caused the death of 12-year-old Tommie Shepherd (also spelled Shepard) (Section A, Row C, Grave 37) (Figure 14) in 1905 reminds us that children were also victim to tragic events (Dallas Morning News 1905; Appendix D).

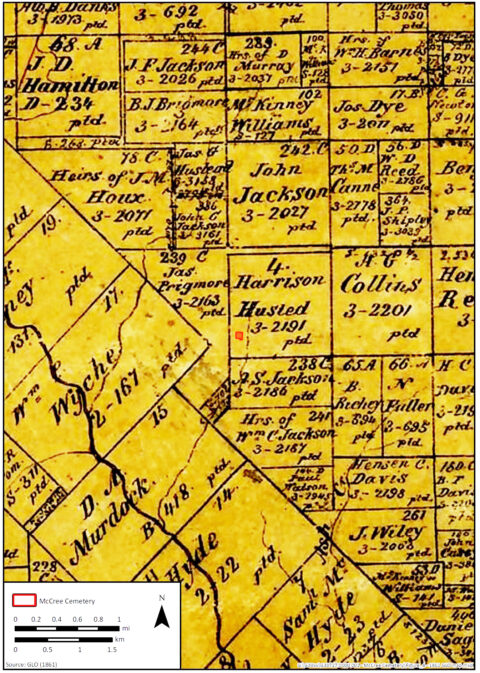

The Establishment of McCree Cemetery

The land on which McCree Cemetery is located is part of the Harrison Hustead Survey No. 587. Hustead, his wife Prudence Bartlett, and their children arrived in Texas to claim land as Peters Colonists. As a family man, Hustead was granted 640 acres in 1850 (Connor 1959:291). The 1850 census lists him as a farmer living with his wife, Prudence, and their eight children ranging in age from 16 to two. Hustead and his family did not stay in the area long, however. He died in 1852 in Lisbon (6 1/2 miles south of Dallas) (FJFa, c).

H. McCree and Mahulda Bonner McCree acquired several acres from the Hustead Survey, including that portion that would become McCree Cemetery. Little is known of the McCree family. E. H. and Mahulda came from Tennessee and were married in Dallas County in 1859. McCree Cemetery was established June 19, 1866, when Mahulda Bonner McCree granted 1.5 acres to William McCullough and James E. Jackson for a public graveyard. It is assumed that E. H. McCree was deceased by then as Mahulda Bonner was the only grantor to sign the deed. The lot was described in the deed as:

“. . . on the waters of White Rock Creek and being out of the H. Houstead [sic] tract on which I am now living and meted and bounded as follows, to wit. Beginning at a stake on high prairie, Wm McCullough’s East chimney . . . being the same land now used as a public graveyard” [Deed Records J:485].

That the area had already served as a place of interment was not unusual. During settlement periods throughout the nation, the necessity of performing a burial often occurred prior to any concerted effort to formally establish a cemetery. Several burials might occur before land was officially deeded for that purpose. The first burial associated with McCree Cemetery was that of John Henry Jones (brother-in-law of William McCullough), though the location of his burial plot is unknown. Jones, who had left to fight in the Civil War, returned home in 1862. Soon after, he succumbed to wounds received in the war. Two years later, Eleanor Elizabeth McCullough, born in 1815, was buried nearby. As is inferred in the deed (i.e., reference to McCullough’s chimney as a point of reference, and the relationship between William McCullough as husband of Eleanor Elizabeth and brother-in-law to John Henry Jones), relatives of the deceased were making this area of Dallas County their permanent home and were intent on formally establishing a burial ground for loved ones (FJFa, b).

It is through deed records that we also learn of a nearby settlement of African Americans: the community of Egypt also known as Little Egypt. On June 25, 1896, J. E. Griffin sold one acre of land adjacent to the east side of McCree Cemetery to three African American men—Jeff Hill, George John, and Monroe Parker—for the sum of $25.00 (Deed Records 204:649). The one-acre tract was designated for, “. . . grave yard purposes for the internment of the colored people of this community.”

Less than a month after the Griffins conveyed land for an African American burial ground, they sold one and 5/8 acres to B. J. Prigmore for the sum of $1.00 (Deed Records 247:444). The land was deeded for “a public burying ground, exclusively.” Thus, just before the turn of the twentieth century, McCree Cemetery came to exist in size and boundary as we know it today.

The landscape of McCree Cemetery remains unchanged over the years, while the surrounding area has transformed from agricultural to residential. In a rare photograph from 1938 at the funeral of Arthur Reese Bryant (Section A, Row A, Grave 74), the surrounding agricultural landscape is apparent (Figure 15). Mr. Bryant was killed in an automobile accident while driving a truck for the gas company.

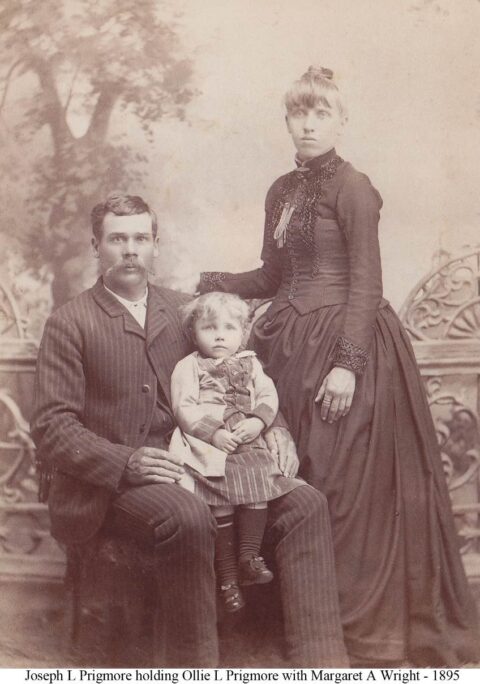

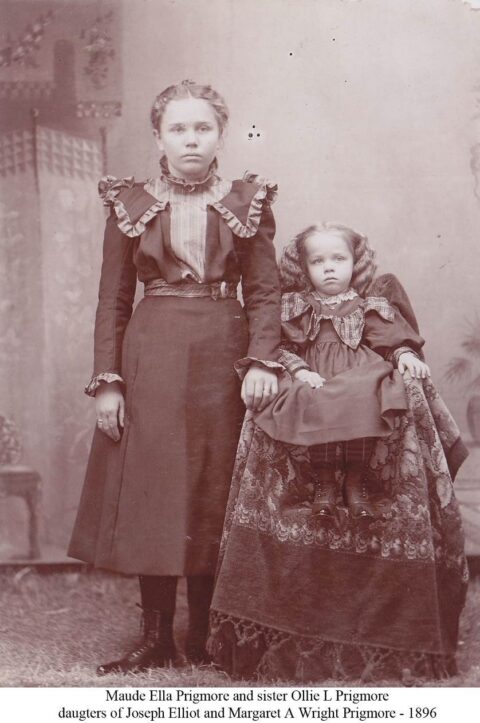

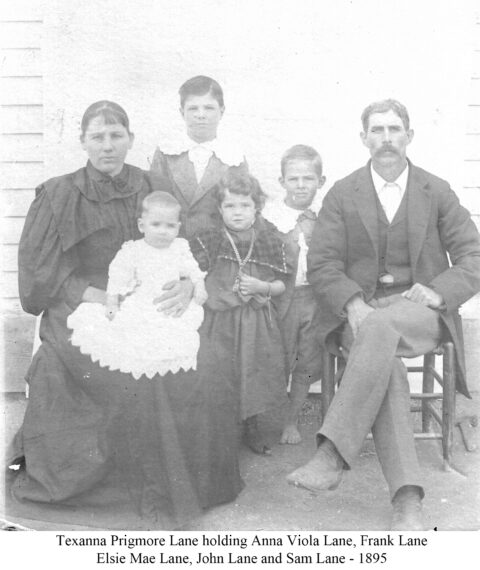

Growth and Development of the Audelia Community

The area surrounding McCree Cemetery remained agricultural for the next 100 years and the built environment that developed reflected the needs of a farming community that grew slowly, but steadily. Beginning with the early settlers and first-generation descendants, homes, roads, bridges, mills, stores, schools, post offices, and churches began to appear. Natural landmarks took on the family names of early settlers and defined the community. To the west lay Jackson Creek and to the east was Dixon Branch—both feeding into White Rock Creek. From the mid-1800s and well into the twentieth century, farms were established throughout the White Rock Creek area. Many, if not most, were established by the sons and daughters of the first settlers—their children intermarrying. Joseph E. Prigmore, son of Benjamin and Nancy Prigmore, was a successful farmer with land just west of McCree Cemetery. He married Margaret A. White in 1885 and they had two daughters, Maude Ella and Ollie (Figure 16 and Figure 17). Joseph was active in local and county politics, and served as an elder in his Presbyterian church. He died in 1940, but was buried at Restland Cemetery (Richardson Echo 1926, 1940). Joseph’s sister, Texanna Prigmore, married Sam Lane. They too remained in the area and raised their family (Figure 18). Sam’s sister, Dora Lane, married Jeff Jackson and they built a house on Audelia Road. Sam’s sister, Sophia (Section A, Row H, Grave 39) also married a Jackson—John T (Dallas Morning News 1916; Figure 19).

Farming was the occupation of choice for the original settlers and many first generation offspring. Nevertheless, both first and second generation descendants began to diversify and some played important roles in the development of nearby Richardson. Tom Jackson Sr., born in 1869, moved into real estate and established Tom Jackson and Sons Realtors. He was also director of the Citizens State Bank, charter member of the Richardson Rotary Club, member of the Dallas Real Estate Board, and finally, served as mayor of Richardson from 1937 to 1947. So beloved was he, that his obituary included this final tribute:

The Echo editor as well as every man, woman and child in this community has lost a friend who was never too tired or too busy to stop and counsel with you and help solve your problems [Richardson Echo 1955].

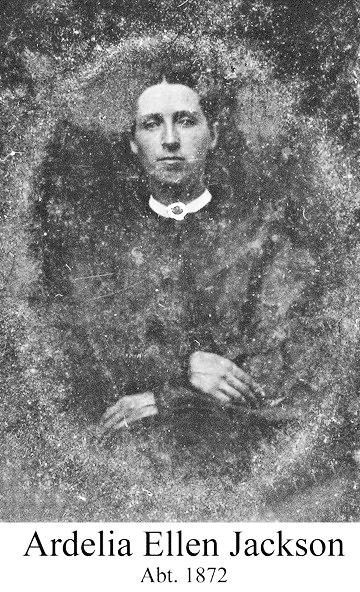

Audelia

The name “Ardelia” began to take hold as the name of the growing nineteenth-century community lying near White Rock Creek. James E. and Diana Jackson had several children, one of them being Ardelia Ellen (Figure 20). Born in 1853, Ardelia married John Frederick West in 1877. John West and his father-in-law built a general store at the southeast corner of today’s Forest Lane and Audelia Road and called it “Ardelia.” In the back of the store was a post office run by a man named Sarver. The mail was brought in and placed on a wooden barrel. There was also a grist mill in the back of the store. Not far from the store, at what would be the northeast corner of Forest and Audelia today, Box Whitfield operated a gin. On the northwest corner, Benjamin Prigmore donated land for the Jackson School. Ardelia Jackson West, along with Sophia Jackson, Dora Jackson, Lena Hoskins, Flo Bank, Minnie Thorp, Sallie Harris, Ben Davis, and a man named Dunlap all taught at the school for $50 a month. Trustees of the school were Will Sharp and Ardelia’s brother, C. W. Jackson (Dallas Morning News 1986).

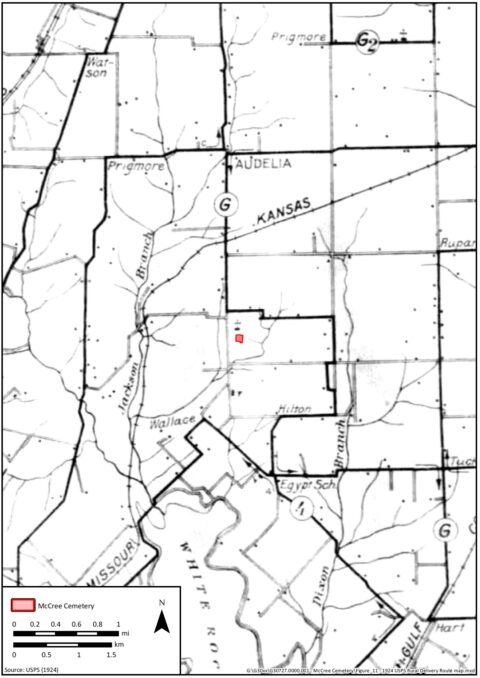

Ardelia died in 1899, and her husband sold the store to George Mercer who owned a farm nearby. In 1904, the post office was discontinued and area residents began receiving mail via rural delivery. At some point, the name ‘Ardelia’ was corrupted to ‘Audelia.’ A 1924 postal delivery map shows the name Audelia, and a 1933 obituary refers to the deceased as having been from the community of Audelia (Dallas Morning News 1904; Richardson Echo 1933; Figure 21).

The Jackson family also lent its name to a small community that existed just north of Audelia, closer to Richardson. Although the Jackson Community was well known, it does not appear to have gained the same prominence as did Audelia. The name does appear, however, in several obituaries which note the deceased was from ‘the Jackson community’ (Richardson Echo 1933, 1954).

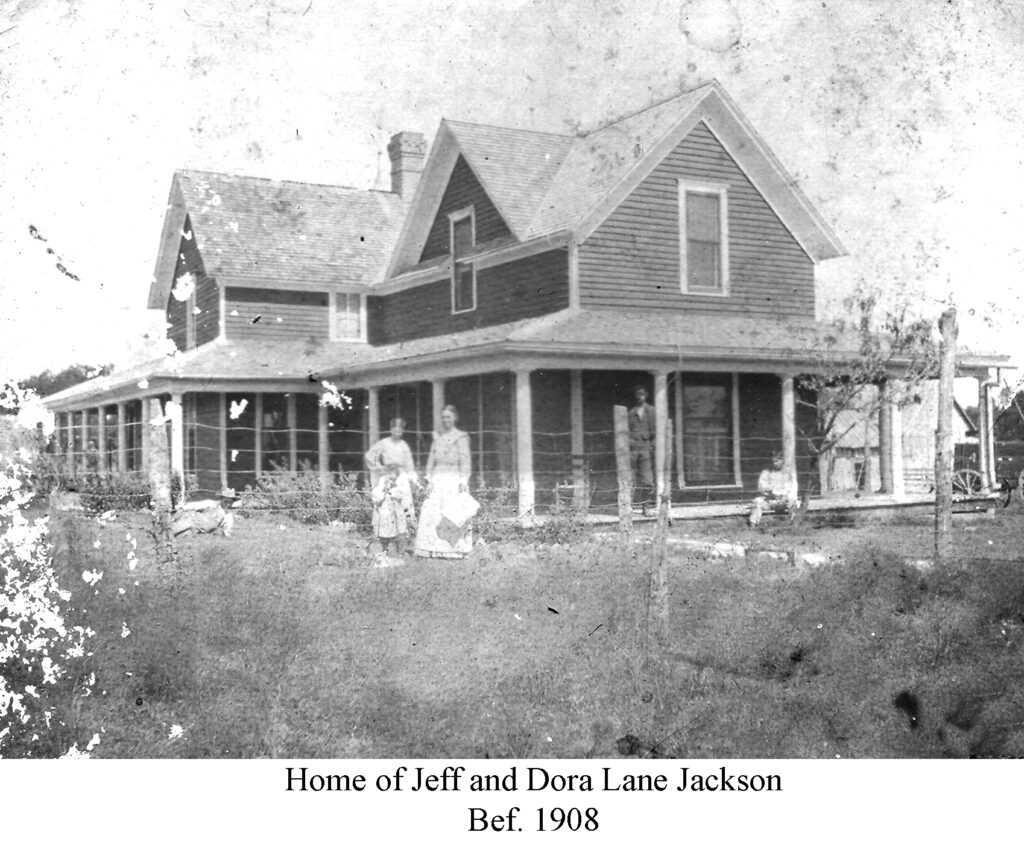

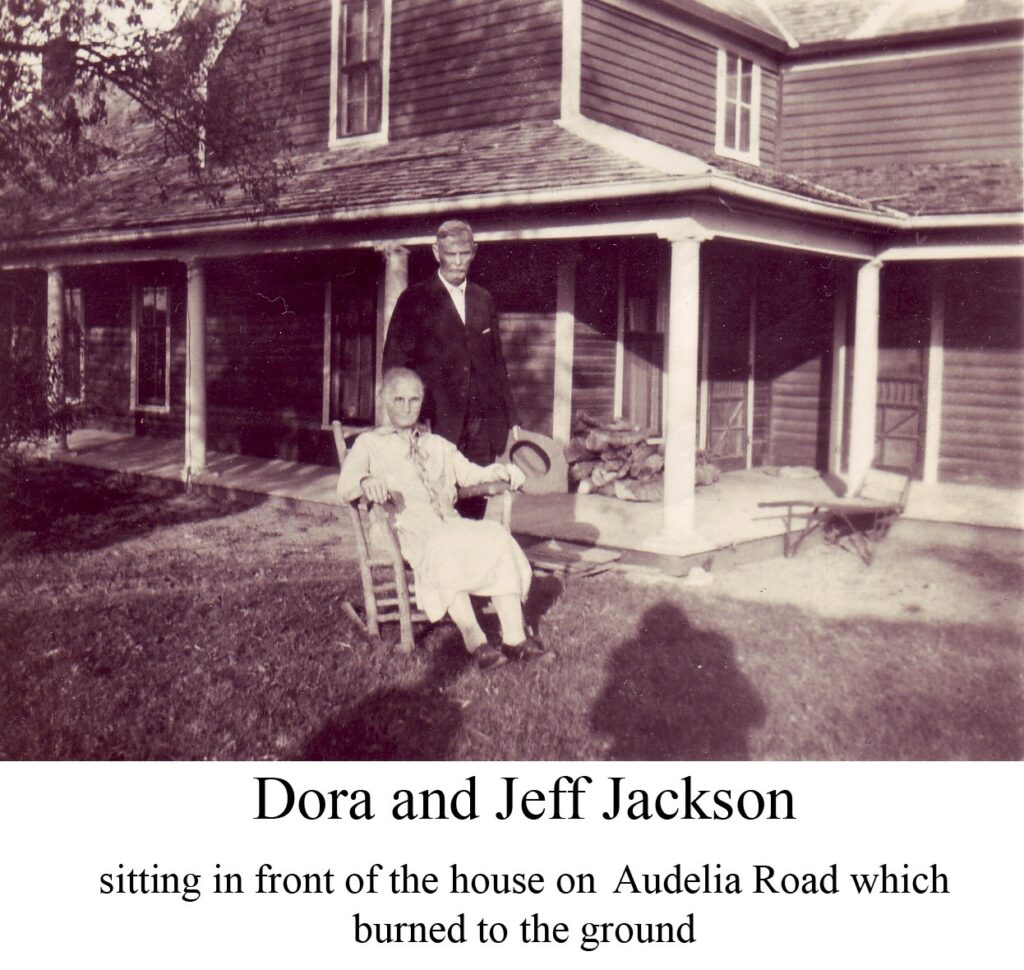

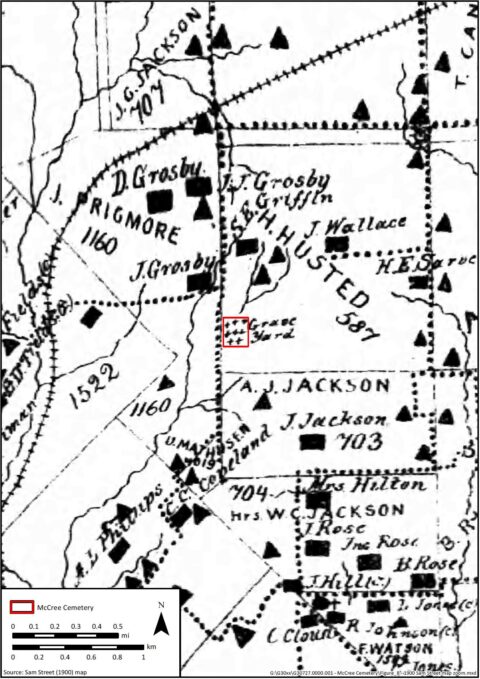

The 1900 Sam Street’s Map identifies the McCree Cemetery and houses belonging to or lived in by several pioneering families and their descendants (e.g., the Prigmores, Jacksons, Crosbys, Griffins, and Wallaces) (Figure 22). The map suggests a rather dense built environment with rectangles being the houses of owners and triangles representing rental properties. The dotted lines are wagon roads; the line with hashmarks is a railroad. Though it cannot be certain that the home of Dora Lane and Jeff Jackson on Audelia Road is typical of the others, a photograph prior to 1908 shows a stately two-story wooden home with a large wrap-around porch and chimney (Figure 23). A later photograph, based on the apparent age of Dora Lane and Jeff Jackson, shows the same house (Figure 24).

Although it is not clear when the Jackson School closed, a 1918 USACE map and 1918 USGS map show the Audelia School located within the same area (Figure 25 and Figure 26). Thus, it is possible that the Jackson School was renamed. At least by 1890, however, there was need for another school. The Rodgers School building was established at present-day Audelia and Parkford on land donated by Campbell Goforth (FJFh). In 1918, a new building was constructed to accommodate state laws (see Figure 25 and Figure 26). The 1918 schoolhouse was described as a one-room, wooden building with windows on the sides. Children sat at desks designed for two students; the room was heated by a pot-bellied stove (DPLa). The Rodgers School district became a part of the Richardson Independent School District (ISD) in 1929. The building remained in its location, however, until the 1950s. At that time, the school house was moved to Vickery, received new siding, and became the Vickery Masonic Lodge Hall (DPLa).

Another addition to the Audelia built environment is referenced October 8, 1929, the date upon which C. W. Jackson, T. B. Crosby, and John Dixon paid $250 to J. D. Robertson for a 1 1/2 acre lease with a frame church building just north of the cemetery lot. By the terms of the lease, said lessees were to maintain the building, and it was to be:

. . . used as place of public worship, by any and all denominations that desire to use said [building], and for services conducted by ministers and others at the burial of the dead in said cemetery. . . Neighborhood meetings may also be held at said building [FJFj].

It was also through this lease agreement that ingress and egress from Audelia Road to the church and cemetery were established. (This later came into play when Southwestern Bell Telephone wished to purchase the land for a parking lot).

Although open to all denominations, it is reported that the church first served, primarily, the Methodists, but on August 23, 1931, the Reverend Charlie Dorman and wife, Mr. J. Dabney and wife, Ms. Francis Dorman, Ms. W. E. Schmitt, and Ms. Gertrude Schmitt organized the Rodgers Baptist Church and used the frame building next to McCree Cemetery for services (FJFa). Because of its proximity to McCree Cemetery, the name Rodgers (or Rogers) was sometimes applied to both the church and cemetery, thus causing confusion over the names of both the cemetery and the community of Audelia. Rodgers Baptist parishioners used the church until 1939 when they established a new building on Jupiter Road (FJFa). The church remained in use, but it was heavily vandalized and intentionally burned in the mid-1940s (see below).

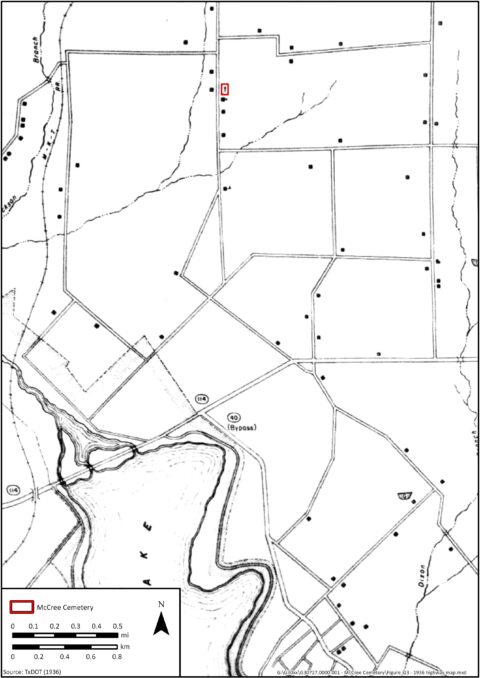

The Works Progress Administration’s guide and history to Dallas noted the population of Audelia as being 35 and that it was “a tiny crossroads village with one store and one church” (Holmes and Saxon 1992:406). This would have been recorded in the mid- to late 1930s. The community was, of course, surrounded by farmsteads as is seen in a 1936 highway map that shows a typical rural built environment separated by wide open spaces (Figure 27).

The reminiscences of a Dallas city resident who visited his grandparents’ farm in the 1930s paints a picture of farm life in this vicinity as it existed during this decade. Robert N. Jones, grandson of Jeff and Dora Jackson, often spent Sundays at their house (the same house shown in Figure 23 and Figure 24). As a child, Jones played in the hayloft, climbed on farm machinery, chased chickens, and waded in the creek, among other things. He also recalled visiting John Jackson’s farm that stood on higher ground near today’s Restland Cemetery and Richland College. There, the flying neon Pegasus atop the Magnolia building in downtown Dallas was visible (Jones 1983).

Add Your Heading Text Here

Jeff and Dora Jackson grew cotton as a money crop but over the years had also sold oats, wheat, corn, and onions. It was said that Jeff Jackson had a way of knowing what crops would be profitable ahead of time. As was common among rural families, Jeff and Dora Jackson were fairly self-sufficient when it came to food. They had pecan trees; a vegetable garden for peas, green beans, and corn; dined on fresh farm eggs; and had a milk cow and fruit trees. They butchered their own hogs on the farm and made a “peppery country sausage” and smoked hams. Although Jeff Jackson’s brother, John, had invested in a plow tractor, Jeff had laborers plow his fields with mules (Jeff Jackson was in his 70s at this time). Jones recalls his grandparents speaking of early trips into “Dallis” to go to the farmers market. They would hitch up a wagon and cross a wide, flat valley that would become White Rock Lake in 1911 (Jones 1983).

In February 1930, Dora Jackson threw a surprise 68th birthday party for her husband. The event was recorded in a Richardson newspaper, noting that the whole family attended, along with Mr. and Ms. Joe Prigmore, and a host of friends who stopped by to wish him well. For Jeff and Dora Jackson, the fruits of their labor came to an end in 1942 when their house burned to the ground. The elderly couple moved to Richardson where Jeff Jackson died in 1944. Dora Jackson died a few years later (Jones 1983; Richardson Echo 1930).

Growth and Development of the Egypt Community

While Anglo settlers were establishing farmsteads in the White Rock Creek area and forming the Audelia community, African Americans were also establishing a community just south of McCree Cemetery where Northwest Highway and Ferndale Road intersect today. After the Civil War, former slaves John (also known as Jeff) (Section B, Row A, Grave 54) and Hanna Hill, and Ephriham (Section B, Row A, Grave 33) and Amanda Floyd (Section B, Row A, Grave 34) established a freedmantown on land that the Hills’ former owner had granted to them. One of several freedmantowns established in Dallas County, this one was christened “Egypt,” a symbolic reference to their exit out of bondage. It is also commonly referred to as “Little Egypt,” though former residents prefer the original name of Egypt (Dallas Morning News 2002; DPLb).

One of the earliest known organizations established in Egypt was the Egypt Chapel Baptist Church. Dr. A. R. Griggs, a prominent minister well known in the North Dallas freedman community near today’s Central Expressway and Lemmon Avenue, organized the church on April 10, 1880. The church itself stood for over 80 years, and it was the only church in Egypt. Photos from 1961 show a one-story frame building 3-bays wide with what looks to be two, two-over-two double-hung windows on each side of the double-wide wood doors. The front of the building has triple, parallel gables. The one side elevation that is visible in the photograph shows at least three windows. According to oral histories from some former residents (see Appendix A), the building was patched and repaired throughout the years; thus, it is unlikely that in 1961 the church looked as it did originally, but nevertheless, it provides a frame of reference for understanding what the community’s single-most important building may have looked like. The building, on the north side of Northwest Highway, faced Ferndale. In addition to the church, there was a one-room school house with blackboards, homemade benches, and a coal stove. The school taught grades one through six (and at times up to the eighth grade). Not only did it serve the children of Egypt, but African American children from miles around attended. The last day of school was fondly remembered. Parents from the country would load up their wagons and bring lots of food to celebrate with speeches, programs, and games. The school was originally located on what would today be the southwest corner of Northwest Highway and Ferndale, but when Northwest Highway was constructed, cutting into the southern edge of Egypt, the school was moved to the north side next to the church. According to former residents (see Appendix A), there was also a dance hall in Egypt. Jeff Hill owned a candy store, and the area was surrounded by peach and plum orchards (Black Churches Network 2015; Dallas Morning News 2002; DPLb).

Children living in Egypt went to school at Alisson Booner, which went from first through eighth grade, and for upper grades they went to Booker T. Washington. Later, Hamilton Park, which was first through twelfth grade, was built, and the children of Egypt went there. The bus came to Egypt to pick up for school that was located near Forest Lane and Central Expressway.

Life in Egypt was a struggle, but it was home and in the words of Jerry McCoy, former resident:

“Life was hard there, but I’ll tell you what, it was one of the blessed things that happened to me. It taught me how to be a man because we didn’t have all the luxuries, but whatever we had, we appreciated. And whatever I get now, I still appreciate” [Dallas Morning News 2002].

Jeff and Hanna Hill had a son, also named Jeff (Section B, Row A, Grave 36), born August 20, 1893. Upon reaching 23 years of age, he registered for the Army and served in World War I. His registration card lists him as a farm hand. He was of medium height, medium build, had blue eyes and black hair. It was also noted that at some point, his right arm had been broken and that it “causes trouble.” Hill enlisted on July 16, 1918, and was discharged August 2, 1919, with the rank of private. Upon his death of stomach cancer on November 5, 1947, he had been holding odd jobs for a living. His wife, Lenora, applied for and was granted a military veterans headstone. Jeff Hill’s headstone is one of the few that remain in the black portion of McCree Cemetery (Jeff Hill 2014).

Vandalism and the McCree Cemetery Association

McCree Cemetery was over 50 years old when a group of descendants formed the McCree Cemetery Association with the intent of preserving and maintaining the burial ground. J. E. Jackson, J. R. Dixon, T. B. Crosby, R. E. Dixon, and A. S. Jackson officially formed the association through the Secretary of State on October 17, 1940. Under the terms of agreement, the corporation was formed to:

. . . promote, maintain, manage, improve, operate and care for the McCree Cemetery, a public cemetery located on the H. Hustead Survey about two miles East of the town of Vickery in Dallas County, Texas, and for the purpose of conducting any one or more or all of the businesses of said cemetery, including the selling of lots therein for burial purposes.

All owners of lots in said cemetery shall be members of this corporation and each owner of a lot or lots embraced in said cemetery shall be a share-holder in this corporation and shall be entitled to all the rights and privileges of a share-holder . . . [McCree Cemetery Association Charter 1940].

The association was chartered for a 50-year existence and was to maintain five directors. The addresses of the five original directors, as noted in the charter, are of interest for the information they provide on the shifting settlement patterns of these Audelia descendants. Some retained rural addresses while others appear to have moved into more developed areas of Dallas. J. E. Jackson and R. E. Dixon both lived on Route 5 of Dallas, Texas. J. R. Dixon lived in Vickery, Texas (a community west of Audelia near present-day Greenville Avenue and Walnut Hill Lane). A. S. Jackson’s address was listed as 4909 Drexel Drive in Dallas. For some reason, the address of T. B. Crosby was not listed.

For at least the first several years, the McCree Cemetery Association sponsored “Decoration Day,” encouraging descendants of those buried there to attend. A 1941 newspaper article announced that the Rev. E. B. Jackson of Prosper would be preaching at a morning service. “Everyone is invited to come and bring a basket lunch” (Richardson Echo 1941). In 1943, two meetings were held; one on November 6 “to discuss maintenance and preservation of the grounds and church.” Another announcement appeared shortly later, for a December 4 meeting when directors for the following year were to be elected. It was further noted that, “This is the day to put out shrubbery, trees and other flowers in the cemetery, and we urge a full attendance” (Richardson Echo 1943a and 1943b). In 1945, a newspaper announcement noted that members of the cemetery association were holding memorial services at McCree “on Audelia Road, a mile north of White Rock Lake” (Dallas Morning News 1945).

An association dedicated to the care of McCree Cemetery could not have come soon enough, though the organization’s control over vandalism was almost non-existent—members seemed powerless to prevent it. Instead, they could only express dismay and concern, but they at least, let others know that there were people in Dallas who cared about the cemetery. For some reason, McCree Cemetery began to attract the attention of young people who liked to party, drink, and vandalize the tombstones and church. It may have simply been that the cemetery was close enough to Dallas, but still isolated. One of the earliest occurrences noted in a newspaper was dated April 28, 1940, when the interior of the church was desecrated and the cemetery was vandalized.

Men and women whose kin are buried in the old Rogers Cemetery [i.e., McCree] on Audelia Road north of White Rock Lake decided to try to repair the old church near the graveyard at a meeting Saturday in the wrecked interior, despoiled by vandals within the last year. The eighty-nine boys and girls whose names were taken by a deputy sheriff one night last March when they were caught at the church and cemetery will first be called on to pay the cost of repairs [FJFi].

The 1950s brought no relief. On October 30, 1950, it was announced that sheriff’s deputies had tried to catch some McCree vandals after people living nearby complained of horns honking and loud voices. It was reported that nearly 70 percent of the tombstones had been knocked over and broken. An article the following day noted that young people threw parties there on Saturday nights, strewing broken beer bottles across the cemetery. The article also noted that five years prior to this, vandals had burned down the frame church and that two years ago, a group of young people congregating at the cemetery had been apprehended. By the early 1950s, the area surrounding McCree Cemetery was owned by J. N. Fannin who reported that the cemetery was still in use and that McCree Cemetery family members were “pretty angry” with the vandals (Dallas Morning News 1950a and 1950b).

The Demise of Audelia and Little Egypt

The vandalism that McCree Cemetery endured in the 1940s and 1950s was deplorable, but the 1960s ushered in changes that had enormous physical and social repercussions on this once-rural cemetery and the surrounding landscape. As the city of Dallas continued to spread northward, the farmland that once surrounded McCree Cemetery gave way to a fashionable, upper middle-class neighborhood, Lake Highlands. A January 1961 plat map shows a cement alley winding its way north and east of McCree Cemetery to provide access to rear-garage-entry homes on Estate and Queenswood lanes. The planned addition that was enclosing McCree Cemetery was called Lake North Estates No. 1. Houses quickly went up with the Lake Highlands neighborhood well established by the mid-1960s. By 1968, McCree Cemetery was completely surrounded with apartments to the south and a telephone office to the west. In 1977, the Southwestern Bell Telephone Company sought to purchase the entryway into McCree Cemetery from the City of Dallas for additional parking. The company was informed that the land was reserved for ingress and egress to the cemetery and the matter was dropped (Dallas City Archives).

Even in the 1960s, the approximate 35-acre Little Egypt community was still served by dirt roads. The houses were dilapidated and most were without electricity; none had running water, indoor plumbing, or gas. The death knell for this freedmantown began when one of the city’s most prominent commercial real estate agencies, Majors and Majors, began eyeing the Northwest Highway/Ferndale intersection for a commercial venture that they christened Northlake Shopping Center. The firm was already the leasing agent for 13 large retail centers, including Wynnewood Village and Ferguson Village (Dallas Morning News 1960). Like Northlake Shopping Center, these two centers remain even today.

On October 31, 1961, developers met at City Hall to seek rezoning (from residential to retail) of the approximate 35-acre tract north of Northwest Highway between Ferndale and Easton. The acreage included Egypt and property owned by few other individuals. It was reported that a number of Egypt residents attended the meeting in support of the rezoning (Dallas Morning News 1961). While it is almost certain that residents held mixed feelings about leaving a community that their ancestors had proudly established, the condition of the neighborhood and their individual homes made the developer’s offer to buy up Egypt to be viewed as a step in the right direction. The patriarch of the community, 89-year-old William Hill, was instrumental in sealing the deal. At least one trustee of the Baptist church believed it was time to leave Egypt “before the entire area faced condemnation proceedings that residents could ill afford” (Dallas Morning News 1962a; 2002).

Households received a minimum of $6,500, enabling them to purchase a modest home with amenities elsewhere. One newspaper article noted that William Hill received $22,000 in cash, though it is difficult to discern if that was more than what most received or if it was an average amount. The developers also paid for the trucks to move the families. For the most part, Egypt residents desired to relocate as a group, though they did ultimately move to one of three areas: Oak Cliff, Garland, or Elm Thicket (an African American enclave near Love Field). The night before the move, Egypt residents gathered at their beloved Baptist Church to pray that there would be no rain on moving day, which would make the dirt roads impassable. On the morning of the move, 37 trucks were lined up to assist 200 families. Following those moving to Oak Cliff was Egypt Chapel Baptist Church, which relocated to Hutchins Road where it exists today. Within a few hours, Egypt was emptied to make room for planned development. There was no rain that day (Black Churches Network 2014; Dallas Morning News 1962a and 1962b; 2002).

McCree Cemetery Today

With Audelia and Egypt gone, McCree Cemetery was virtually the only physical reminder that either community once existed. Yet it lay hidden amongst the trappings of a mid- to late twentieth century landscape. It was not forgotten, however—not by vandals, nor by descendants and others who cared about the final resting place of those before them. In the 1960s and 1970s, those who lived on Estate and Queenswood lanes remember a cemetery in disarray with broken tombstones, beer bottles, and trash. The cemetery was still active, however, with burials occurring in both the white and black sections. Descendants, and others, could no longer tolerate the neglect that this cemetery had received for the past 40 years. In 1985, Shirley Caldwell, Chairman of the Dallas County Historical Commission, received a letter from the Texas Historical Commission (THC) in reference to her application for a McCree Cemetery marker. Information collected by Mary Sutherland (niece of Ardelia Jackson West and member of the McCree Cemetery Association), Jimmie D. McSween (a McCullough-Jones descendant), Frances James (local historian and expert on Dallas County cemeteries), and most likely others, contributed to the information on the marker that graces the entrance to McCree Cemetery today. A program to dedicate the marker was held on April 6, 1986. Accepting the marker were Dr. Mable Maxey, a professor at Texas Women’s University and descendant of William McCullough, and Everts Earl Jackson of Richardson, a descendant of James E. Jackson. Jackson and Dixon descendants Shannon Cammuck, Jennifer Cammuck, Ginney Derryberrry, and Delisa Carney had the honor of unveiling the marker. Glenda Cammuck provided a history of McCree Cemetery. Fittingly, Rev. Charles Thomas of Rodgers Baptist Church gave the invocation and dedication. The Lake Highlands Women’s League and the Lake Highlands Republican Club sponsored a reception following the dedication (FJFk).

The assimilation of McCree Cemetery descendants and Lake Highlands organizations for the marker dedication demonstrates a connection between past and present that is still acknowledged today. Those whose ancestors once farmed the fields and those who represent the residential urban wave that followed recognize a shared sense of place that is symbolized by this small, prairie cemetery.

Today, McCree Cemetery remains a historic feature of the community. While the cemetery is no longer active, descendants, the local community, and organizations such as Preservation Dallas want to ensure its future as a resting place for Dallas early pioneers and as a historic site for future generations. Lake Highlands neighbors still keep an eye on it, and Lake Highlands organizations and businesses are involved in its future. Preservation Dallas, with funds from the B. B. Owen Trust, has undertaken efforts to secure city landmark status. Sadly, the havoc wreaked by vandals remains, but knowing the cemetery’s history and maintaining this small parcel of prairie land is a way of giving thanks to those before us. In the 1800s, Benjamin Prigmore explained that this small rise of land was chosen as a burial ground because it was the prettiest spot in the area. He was right then, and he is right now.